A History Of Social Housing In The UK

The provision of social housing boasts a long, rich, yet up-and-down history in the UK, going back as far as both world wars. Housing has been a constant priority for governments, and continues to be today. This article examines the acts that were passed by governments to provide housing for all, clear slums and close the gap between the rich and poor, as well as addressing barriers that were faced in the wake of housing plans. This important history has influenced housing and property as we know it today.

In pre-war Britain, buying a house was reserved for the very wealthy and taking out loans for mortgages from banks was uncommon. However, as the population increased, more and more people started relocating to the big cities for work, and pushed into over-crowded inner-city slums. These slums caused public health concerns, especially from the middle class who were worried about the spread of disease.

Therefore, the government recognised a need to provide new homes for the poorest sectors of society and to replace the inner-city slums with better quality housing.

The first effort to provide social housing was the ‘1890 housing for the working classes’ Act. This act granted local authorities power to shut down unhealthy slum housing and made landlords more liable for the health of their tenants, by setting standards of health to be met. Efforts was made to build and regulate private Common Lodging Houses that catered for those in need. These were known as the first council houses in the world.

Photo credit: Shahid Khan/Shutterstock

World war 1

During world war 1, building costs had inflated and there was a lack of building materials. Consequently, fewer building works took place and the country faced a housing shortage. It became a government priority to build new houses.

The Government felt particularly responsible for providing homes for the soldiers returning from war. This lead to the ‘Homes fit for Heroes’ Act in 1919, also known as the Addison Act, after Minister of Health, Dr Christopher Addison.

The act promised government subsidies to help finance the construction of 500,000 houses within three years. However, as the economy rapidly weakened in the early 1920’s, funding had to be cut, and only 213,000 homes were actually completed under the Act’s provisions.

High quality garden estates were built, usually on the outskirts of cities. Although these provided nice homes for some; these were still too expensive for the most needy.

Photo credit: Everett Historical/Shutterstock

World War 2

Again there was a halt in the build of new homes and England yet again faced a housing and building materials shortage. Houses were bombed in the war, and left a shortage of 750,000 homes.

Prime Minister at the time, Winston Churchill, made housing central to his government. He ordered for the build of temporary homes; known as pre-fabricated homes. These were quick and easy to build, and contained fully-fitted kitchens and bathrooms, unlike houses built beforehand.

Despite only being temporary fixes, supposed to last approximately 10 years, prefabs were popular and a few are still in existence today.

Pre-fab home in Cardiff Philip Bird LRPS CPAGB / Shutterstock.com

Housing central to government

1950s

Terraced houses 1958 – Photo credit: Philip Capper/ Wikimedia Commons

The 1950’s saw the peak of production of houses; 45 families per week were being housed. The government needed another quick and cheap method of building houses that were more long lasting than the ‘pre-fab’. They also needed to be easier to construct, as England faced a skills shortage. This resulted in pre-cast reinforced concrete houses (PRC’s), housing the generation of ‘baby boomers’.

Thirty years later it was discovered that the materials used to build houses were liable to deterioration of reinforcing steel and the cracking of concrete panels; as they were extremely cheap. Subsequently, houses stopped being made from these materials.

Photo credit: Jonathan Billinger/geograph.org.uk (commons.wikimedia.org)

The streets in the sky

During the 1950’s and 1960’s pre-fabricated high rise blocks (known as ‘streets in the sky’) started popping up over the UK, replacing poor quality rows of terraced houses. They were cheap and easier to build, and helped to alleviate the then current problem of overcrowded houses. The government was providing subsidies for blocks higher than 6 storey’s, which meant that developers had an incentive to build higher blocks. Neighbourhoods’ around the country were being demolished and rebuilt with mixed estates of high and low-rise buildings.

Councils had the power of ‘slum clearances’ which meant they could control and purchase land for housing developments, and houses could be demolished for new developments; although some communities fought and protested against this.

Photo credit: Chris Upson/geograph.org.uk (commons.wikimedia.org)

By the 1960s, over 500,000 new flats had been added to London’s stock. These housed the rising population.

Unfortunately, these blocks of flats weren’t very well constructed; the structure and design was poor and so many of them needed constant repairing and maintenance. A notable example is the collapse of some of the Ronan point, following a gas explosion, which caused a plunge in confidence in high-rise buildings. Thankfully this lead to changes in building regulations.

Ronan point collapse 1968. Derek Voller/ Geograph.

1980’s

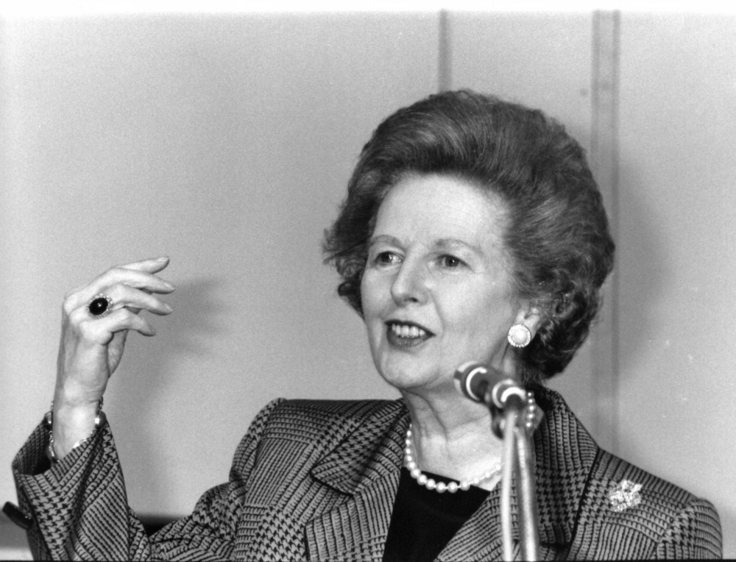

In the 1980’s, Margaret Thatcher’s government implemented the ‘Right to Buy’ scheme, which gave those living in council houses the ability to buy their homes at a huge discount; 1 in 3 were able to buy. By 1987, more than 1,000,000 council houses in Britain had been sold to the tenants, and for some who sold on their council houses, made a healthy profit years later.

The legislation was put in place as it reflected the ingrained British desire to own a home. It would also mean homebuyers would take more pride in where they lived, and many of the unattractive buildings would be improved and modernised.

Although extremely positive for some, it did leave the house stock with a lack of social housing for those who could not afford to buy. Most of the homes that were sold were houses rather than flats which meant that there was a reduced supply of family homes. Many of the old poor quality PRC’s were impossible to sell fast due to their major structural problems.

The situation today

In 1979, 42% of Britons lived in council homes. Today that figure is just under 8%. The UK finds itself faced with a stock of older council houses that were built in the 1960’s and 70’s and desperately need to be brought up to modern living standards. With a huge population of around 64 million, the UK’s need for houses, in particular affordable houses, is ever present today.

These properties require lots of maintenance to keep them up to date, due to their poor build and design. They also need to be made more attractive and more in-line with modern taste.

Recent governments have made some efforts to regenerate older properties. In the past 10 years, 50 former council estates across London have been granted planning permission for substantial regeneration attempts. Examples of this are: 2,760-home estate regeneration in Hackney and the Grahame park estate regeneration in Barnet.