Historical Property Prices vs What That Money Buys You Today

With the average house price in the UK sitting at £269,000 for 2025, many people are perplexed staggered that you could once buy a property for hundreds of pounds.

As the UK grapples with an increasingly unaffordable property market, a look back at historical house prices reveals just how stark the transformation has been. What could once buy you a family home now barely covers the cost of a basic appliance or a plane ticket.

In this nostalgia-fuelled deep dive, we compare the average UK house price by decade with what the equivalent amount of money can buy you today. Brace yourself for a journey through time and inflation that might leave you shocked, amused, and perhaps a little wistful.

1930s: A home for £600

Average house price: £600

Equivalent today: LG 9KG washing machine

In the early 1930s, during the shadow of the Great Depression, the average house cost just £600. This amount would now barely get you a mid-range washing machine. Back then, £600 could buy you a comfortable family home in a town or village. Today, it might save you a few trips to the launderette.

This decade marked the beginning of mass residential development, with many semi-detached homes built to accommodate growing families. Housing was seen as a practical investment, not the financial juggernaut it has since become.

1940s: £1,884 and a World War later

Average house price: £1,884

Equivalent today: Annual London Zone 1 Travelcard

Post-war Britain faced a housing crisis, but property remained relatively affordable. For under £2,000, you could buy a home. Today, that amount gets you a single year’s unlimited travel in Central London Zone 1.

The 1940s were marked by government rebuilding schemes, with the rise of council housing and prefabs. Homeownership wasn’t widespread yet, but it was within reach for the middle class.

1950s: The Baby Boom and affordable homes

Average house price: £1,891

Equivalent today: Samsung American-style smart fridge freezer

With post-war prosperity, the 1950s saw a boom in housebuilding. Homeownership began to increase steadily. For the price of a modern smart fridge today, you could purchase a modest home in a pleasant neighbourhood.

Societal expectations were different too: one breadwinner per household could often afford a mortgage. Compare that to today’s dual-income norm, and the affordability gap becomes painfully obvious.

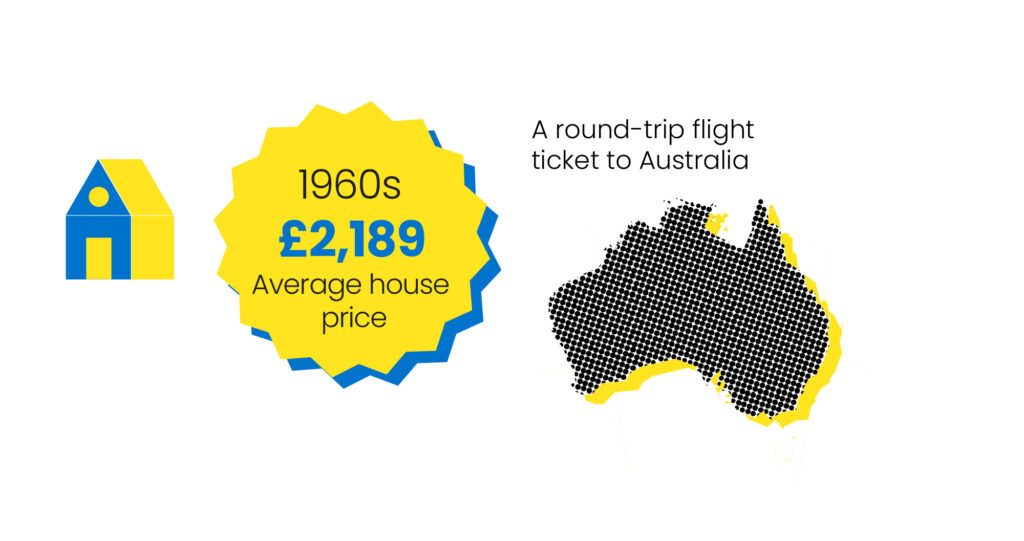

1960s: Swinging London and optimism

Average house price: £2,189

Equivalent today: A round-trip flight ticket from Heathrow to Sydney

As the cultural revolution took over the UK, owning a home still cost less than an international plane ticket does today. The 1960s were a time of growing optimism, and the government heavily invested in social housing.

The ratio of house price to income was still manageable. People bought homes to live in, not as projected investments. The housing market was stable, supported by secure employment and relatively low borrowing costs.

1970s: Inflation and the oil crisis

Average house price: £4,057

Equivalent today: Apple MacBook Pro 16” and laptop case

Despite the economic turbulence of the 1970s, including rampant inflation and oil shortages, house prices remained relatively low. In today’s money, the cost of a high-end laptop in 2025 could have secured you the keys to a three-bedroom house.

Property was increasingly seen as a desirable asset, but it hadn’t yet become the goldmine it is today. The average worker could still afford to buy a house within a couple of years.

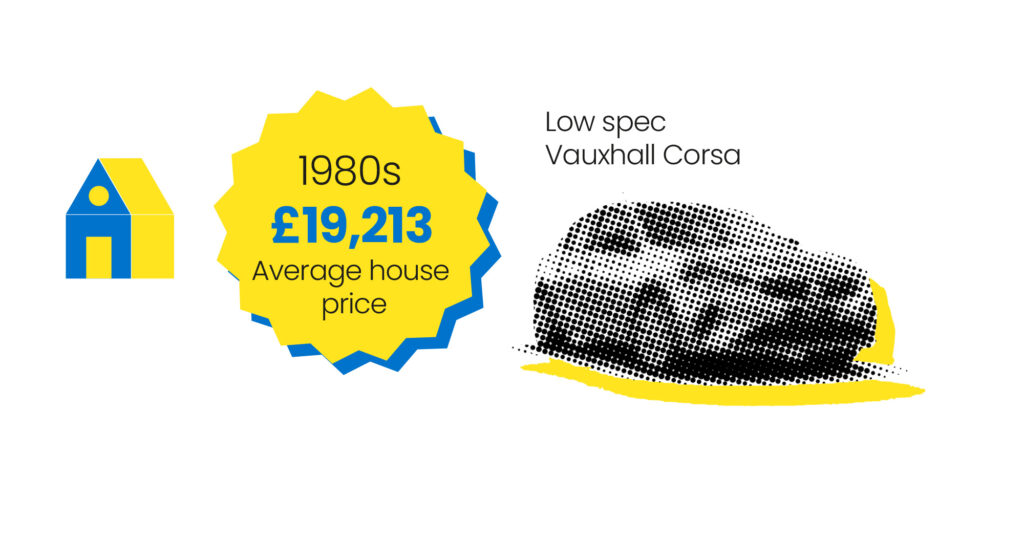

1980s: Thatcher, council house sales and climbing prices

Average house price: £19,213

Equivalent today: Low spec Vauxhall Corsa

The 1980s were a watershed moment in UK housing history. Margaret Thatcher’s ‘Right to Buy’ policy changed the housing landscape, allowing council tenants to purchase their homes at a discount. This drove homeownership to new heights.

A home that cost under £20,000 back then might now be worth ten times as much. And what would £19,213 buy you today? Not much more than a basic Vauxhall Corsa. The era that marked the birth of aspirational homeownership also sowed the seeds of today’s affordability crisis.

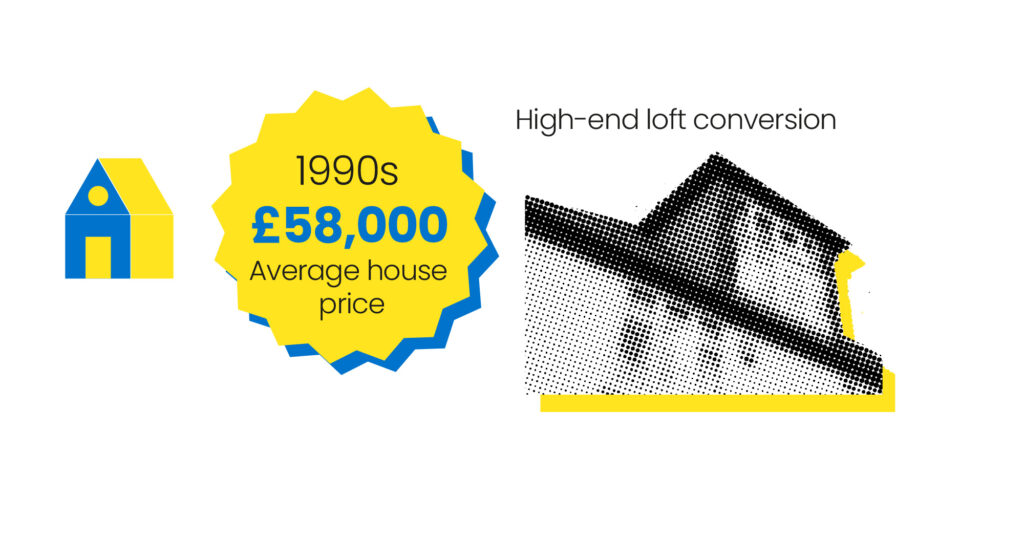

1990s: The boom before the bust

Average house price: £58,000

Equivalent today: High-end loft conversion

With economic recovery in the mid-90s came a housing market resurgence. Property was increasingly seen as an investment vehicle. House prices rose significantly, and by the end of the decade, the average UK home cost around £58,000.

That amount today might cover the cost of a luxury loft conversion, adding space to an existing home but nowhere near enough to buy one outright. The disparity between then and now was rapidly widening.

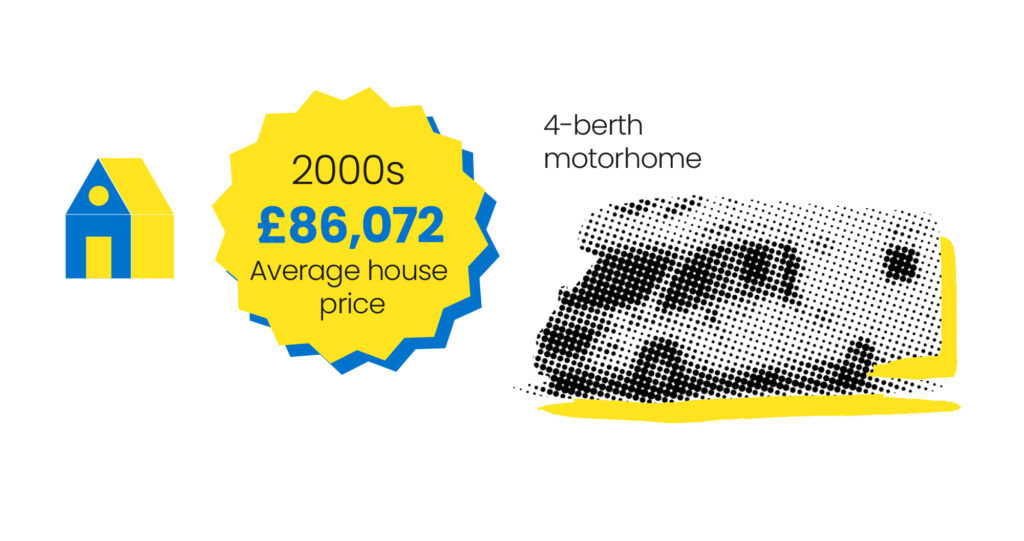

2000s: The property ladder gets steeper

Average house price: £86,072

Equivalent today: Elddis Avante 4-berth motorhome

The new millennium ushered in an era of spiralling house prices. Fuelled by low interest rates, relaxed lending standards, and buy-to-let booms, prices skyrocketed. A typical house cost around £86,000 in 2000. Today, that sum might buy you a comfortable motorhome – a far cry from bricks and mortar.

By the end of the decade, the 2008 financial crisis exposed the fragility of the housing bubble. Yet, prices never truly returned to pre-boom levels.

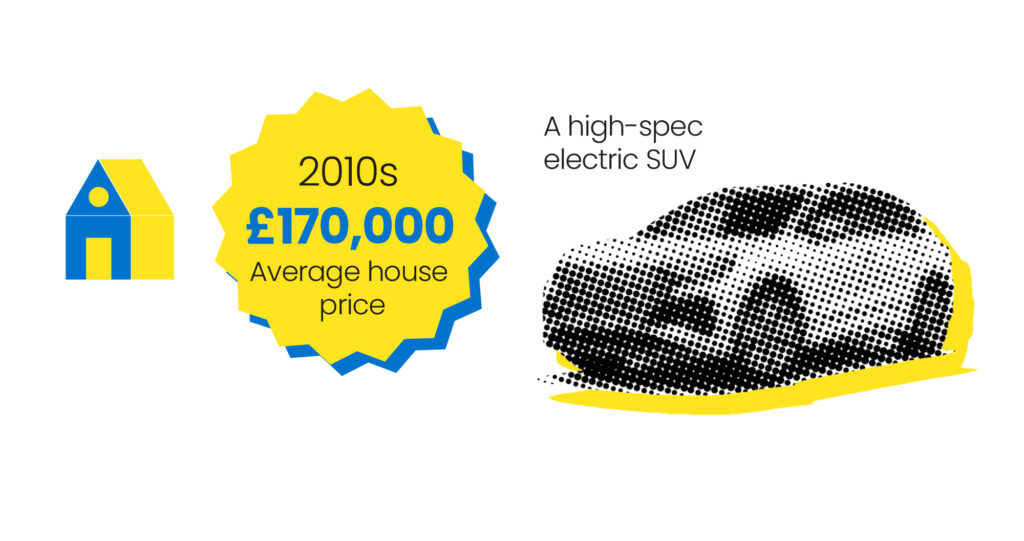

2010s: A decade of recovery and renters

Average house price: £170,000 (2010) to £220,000 (2019)

Equivalent today: A high-spec electric SUV

The 2010s saw prices rebound and surge. Government schemes like Help to Buy and a chronic lack of supply kept demand strong. In 2010, the average home cost around £170,000. By 2019, it had climbed to over £220,000.

Millennials found themselves priced out, leading to the rise of Generation Rent. With prices still climbing faster than wages, even solid earners struggled to break into the market. The same amount of money could now buy you a luxury electric car – not a home.

2020s: Pandemic Property Boom

Average house price: £285,000 (2023)

Equivalent today: A year at an elite private school for two children, or a 2-bedroom flat deposit in London

Despite a global pandemic, the UK housing market surged. Remote work drove demand for larger homes, while low interest rates and a stamp duty holiday poured fuel on the fire. By 2023, the average house cost nearly £300,000.

The amount might secure you a deposit on a small London flat, or fund major lifestyle changes. But full ownership? Still elusive for many first-time buyers.

The big North vs. South property price comparison

While national averages tell one story, regional differences reveal an even deeper divide – one that’s reshaped the UK’s housing landscape over the decades. The North-South divide in property prices has become a defining feature of the housing market over the past few decades. In 1980, a house in London would cost you about double what one in the North East would. Fast forward to 2025, and that gap has ballooned to nearly four times the cost.

1980 vs 2025

- 1980:

- London: £25,000

- North East: £11,000

- 2025:

- London: £525,000+

- North East: £130,000

The contrast in price illustrates not only the rapid increase in property values but also the enduring role of London as a global financial powerhouse, drawing investments, jobs, and talent from across the country and beyond. Meanwhile, the North East, traditionally one of the UK’s industrial heartlands, has faced slower economic growth, with property prices reflecting that slower pace.

These growing price gaps haven’t just stayed on paper, they’ve driven real, significant shifts in where people choose to live.

Migration and affordability

Over the years, the North-South divide has fuelled a significant migration pattern – particularly of younger people and professionals. Faced with skyrocketing property prices in London and the South East, many individuals and families have been forced to look further afield, seeking out more affordable hoe in cities like Manchester and Liverpool. As a result, these cities have seen significant growth, both in population and property demand.

However, while northern cities offer more affordable housing, they haven’t always been able to match the wage growth seen in the South. While you might find a three-bedroom semi-detached house in the North for £130,000, wages in many northern regions are still lower than in London, meaning that even affordable housing becomes a stretch for many.

This growing affordability gap has created a two-speed economy – one where southern regions benefit from high property prices, while northern regions struggle with stagnating wages and a lack of investment in key industries. Over time, this difference has led to a situation where people are finding it harder to build wealth through property ownership, particularly in the North.

Economic and investment trends

The difference between the North and South also extends to investment trends, on both a personal and institutional basis. London’s property market has historically been seen as a safe bet, attracting investment from high-net-worth individuals and developers. The capital’s market is sustained not just by domestic demand but by global capital seeking safe havens for investment. On the other hand, while northern cities offer better value in terms of property prices, they lack the same level of high-investment appeal.

Recently, however, there has been a push to rebalance the UK economy, with government initiatives like the ‘Northern Powerhouse’ aiming to boost infrastructure and attract investment to northern cities. While these efforts have had some success in fostering economic development, they have yet to fully bridge the property price gap.

The impact on homeownership

For many aspiring homeowners, this regional disparity means that owning a home in London or the South is increasingly out of reach. The proportion of people in their 20s and 30s who can afford a home in the South has sharply declined, with many now facing the grim reality of having to rent indefinitely. Conversely, in the North, while houses remain more affordable, the inability to secure higher wages means homeownership remains elusive for many.

The ongoing North-South divide poses significant challenges for policymakers. While addressing the housing crisis requires a national response, the regional nature of the problem calls for a tailored approach that considers local economic conditions, wage growth, and property market dynamics.

Changes in mortgages and interest rates

If house prices have skyrocketed, so too has the way we finance them. From high-interest rates of the 1980s to today’s extended mortgage terms, the borrowing landscape has evolved in ways that reflect (and often exacerbate) affordability issues.

1980s: High interest rates and strong incomes

In the 1980s, the UK saw some of the highest interest rates in history, peaking at around 15% during the early part of the decade. This was largely due to inflationary pressure and attempts on the part of the government to curb rising prices. While housing prices in the 1980s were kept relatively modest, interest rates meant that the monthly mortgage bill could be equally as expensive as today.

A first-time buyer in 1985 might have been required to pay monthly mortgage instalments that absorbed a large percentage of their salary, even when purchasing a £20,000 house. Most of these mortgages also had relatively short terms of repayment of around 15 to 20 years, so the monthly burden was heavier for borrowers. In the 1980s borrowing was usually only accessible to individuals with solid, stable incomes, and the higher the LTV ratio, the higher the repayment obligations.

Despite these costly monthly payments, homeownership still remained feasible for most, as the relatively low house prices meant people could save up for a deposit and secure a mortgage, although at some level of financial compromise.

Today: Lower interest rates, higher property prices

Fast forward to today, and mortgage rates have declined significantly, with the majority of lenders charging between 4% and 6%. At first glance, this appears to be a reprieve for house buyers, particularly when compared to the 1980s. However, this drop in interest rates has been accompanied by an enormous surge in house prices.

The average UK house price today is over £250,000. While mortgage payments are maybe slightly less now than their share of interest rates in the 1980s, they are still considerably higher in absolute terms. The average mortgage to purchase a £250,000 home today, even at the relatively low rate of 4%, can be monthly payments many first-time buyers cannot afford.

For most young buyers, what this means is that while interest rates are lower, the weight of having to borrow has only been compounded by increasing property prices.

Longer mortgage terms

One of the most significant changes in mortgage practices is the increase in the typical mortgage term. Where once 25-year mortgages were the norm, today many homebuyers are opting for much longer terms and even lifetime mortgages. While this extends the period over which borrowers repay their debt, it also reduces the monthly payment amounts, making homeownership feel more accessible in the short term.

This shift is not without its downsides. A 35-year mortgage, for instance, would mean that many homebuyers are still paying off their homes well into their 60s or 70s, when they should ideally be focusing on retirement. Essentially, while a long mortgage term makes monthly payments more manageable in the short term, it keeps people in debt far longer, reducing their long-term financial flexibility.

Moreover, this also increases the total amount paid over the life of the loan. As interest compounds over such extended periods, buyers can end up paying much more for their property than the original asking price – in some cases, hundreds of thousands more.

Deposit requirements

Mortgage payments are a secondary concern to the deposit for most. In previous decades, a 10% deposit was the norm. This meant that for a £20,000 house in the 1980s, you’d need to save up just £2,000, an achievable goal for many individuals with stable jobs.

Today, the situation has changed dramatically. In many parts of the UK, particularly in London and the South East, buyers are now expected to provide much larger deposits. Many lenders require at least a 15–20% deposit, which means a first-time buyer looking to purchase a £250,000 home might need to save upwards of £50,000. For many this can seem like an impossible task.

The rising deposit requirement has placed even greater pressure on the housing market, further locking out those who do not have access to family wealth or other financial support. This is particularly problematic for first-time buyers, who face a triple threat of high house prices, high deposit demands, and the challenge of securing long-term financing.

The role of government schemes

In response to the affordability crisis, the UK government has introduced a variety of schemes aimed at easing the financial burden on homebuyers. Programs like Help to Buy and Shared Ownership have been designed to assist people who struggle to save for a large deposit or who cannot afford a full mortgage on their own. These programs have helped many get a foot on the property ladder, but they are not a solution for the affordability problem.

For example, Help to Buy allows first-time buyers to purchase a new-build home with just a 5% deposit, with the government providing an equity loan for up to 20% (or 40% in London). While this has made homeownership more attainable for some, it also means that homebuyers are entering the market with a greater level of debt and often have to contend with higher monthly repayments once the loan is paid back.

The broader picture

Ultimately, the changes in mortgage rates, terms, and deposit requirements reflect the evolving relationship between wages, property prices, and financial systems. While lower interest rates have made it easier for some to borrow, the financial strain of high house prices and large deposits has made it increasingly difficult for the average person to achieve homeownership. Meanwhile, longer mortgage terms and rising levels of debt mean that those who do make it onto the property ladder are more likely to remain in debt well into their later years.

As housing prices continue to climb, and with inflation continuing to put pressure on wages, it remains to be seen whether the mortgage market will evolve further to address these challenges – or if we’ll see an even greater divide between those who can afford a home and those who are locked out of the market entirely.

House prices vs wages

Beyond borrowing costs and property values, a more fundamental issue looms, the widening gap between wages and house prices

The relationship between house prices and wages has shifted dramatically over the decades, resulting in an affordability crisis that has left many people, especially younger generations, struggling to get onto the property ladder. The skyrocketing cost of property has vastly outpaced the growth of wages, creating an ever-widening gap between what people can afford to buy and the reality of what the housing market demands.

A more affordable market (1970s)

Back in 1970, the housing market was in a very different place. The average house price in the UK was around three times the average annual salary. With an average salary of around £1,700 per year, you could expect to pay approximately £5,000 for a home. In many parts of the country, including areas outside of London, buying a home was attainable for most middle-class families, often with just one income. The affordability of property meant that, even with modest wages, many could save enough for a reasonable deposit and secure a mortgage that didn’t overextend their finances.

Back then, it wasn’t uncommon for young adults to secure their first home in their 20s. Homeownership was a realistic and achievable goal, and the financial burden was far less daunting than it is today. Of course, wages were lower too, but the proportion of income spent on housing was manageable, allowing families to thrive even with limited incomes.

A widening gap

Today the average house price in the UK is now more than eight times the average annual salary. With house prices exceeding £250,000 and average salaries around £30,000 to £35,000, homeownership is out of reach for many, particularly for first-time buyers or those from lower-income backgrounds. In some high-demand areas, especially in London and the South East, this ratio is even more extreme, with properties costing ten times or more the average income.

This massive increase in house prices has created a generational divide. Younger people, many of whom are still burdened by student debt, high living costs, and lower relative wages, find themselves unable to afford even modest homes. Meanwhile, older generations who bought property when prices were lower are sitting on a substantial amount of wealth – often the result of appreciating house prices over the years. This disparity has sparked increasing frustration among younger buyers, who see homeownership slipping further and further out of reach, while their parents’ generation is sitting on properties that have dramatically appreciated in value.

Wage stagnation and affordability

The relationship between house prices and wages has been shaped by wage stagnation. While house prices have soared, wages have not kept pace. In the 1970s and 1980s, wages generally grew in line with the cost of living and the housing market. In recent decades wage growth has been sluggish, particularly after the 2008 financial crisis.

This growing disparity means that homebuyers today are faced with the harsh reality of having to either compromise on location, size, or quality of the property they can afford, or face the grim prospect of never owning a home at all. In areas like London, where house prices have become even more inflated, many people are choosing to rent indefinitely, while those who manage to scrape together a deposit are often saddled with massive debt over extended mortgage terms.

The Bank of Mum and Dad

With the unaffordability of the housing market, the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ has come into play. The phrase refers to the financial support provided by senior family members to help first-time buyers secure a home. Whether it’s covering part of the deposit, co-signing a mortgage, or even buying property outright for their children, family support has become a crucial factor in enabling many young people to buy a property.

Research from Zoopla reveals that, on average, parents are shelling out £58,000 to help their children afford a home. This trend highlights the generational divide, and the growing difficulty younger people face in entering the property market without family assistance. However, not every young person has this option. For those without parental wealth, the dream of homeownership is becoming increasingly distant.

The Bank of Mum and Dad has also had the unintended consequence of widening the wealth gap, as only those with affluent parents or family support can afford to buy a home. It places a heavy burden on those from less wealthy backgrounds, perpetuating inequality in terms of access to property and wealth accumulation.

The generational divide

The affordability gap has created a situation where homeownership is no longer the norm. The younger generations are facing greater hurdles to purchasing homes, while older generations are benefitting from wealth and equity generated by years of property ownership. This state of affairs is likely to exacerbate the generational divide, as those who already own property continue to see their wealth grow as property prices increase, while those trying to get a foot on the ladder are left struggling.

The reliance on the ’Bank of Mum and Dad’, longer mortgage terms, and government schemes highlight the extent to which the housing market has become out of reach for many. The result is that large numbers of the population are left private renting, remaining with family, or trying to secure social housing, both of which lack supply.

Nostalgia, reality, and what comes next?

Looking back, it’s tempting to feel nostalgic for a time when homeownership felt within reach for most. While times were different, and average incomes were also lower, the proportion of income spent on housing was vastly more manageable.

Today, a growing number of Brits are being priced out of homeownership. The comparisons made in this piece highlight not just inflation but a structural shift in housing policy, lending practices, and societal values.

Jack Malnick, property expert and MD of Sell House Fast shared his insights on the changing face of homeownership:

The UK property market has changed dramatically over the last few decades. What used to be a realistic goal for single earners has now become a struggle, with most buyers needing two incomes, large deposits, and longer mortgage terms just to afford a home.

Historic comparisons show just how far out of reach the average home has become – and highlight deeper economic problems. For many young buyers, homeownership is no longer a step toward financial security but a growing financial pressure.

Unless house price growth slows to match wage increases, we’re likely to see even fewer people able to buy – especially in London and the South. The solution isn’t just building more homes. We need the right types of homes, in the right locations, with a clear focus on affordability and long-term stability.

If you’re looking to navigate this challenging market, whether to sell your property fast or explore your options, Sell House Fast offers a reliable, hassle-free route to unlocking the value in your home. Get a quick cash offer and avoid the unpredictability of the open market today.